Russell and Norvig: Games (ch. 5)

This note will cover the games modules.

I. Introduction

- Games make a good environment for AI. Can represent the entire game as a state: “represent the game as a search through a space of possible game positions” (Norvig and Russell).

- As opposed to search and MDP’s, we now have an adversary “opponent” to account for.

- Introduces uncertainty into the problem. However, expect that opponent will try to make worst move for the agent.

- Can represent games as a search tree. However, hard to solve. Chess has branching factor of \(35^{100}\).

- Thus, instead of solving a problem via a closed-form algorithm, we will have to make guesses along the way based on past information.

- Efficieny is key.

- To this end, we will learn about:

- Pruning: allows us to ignore portions of the search tree that make no difference to the final choice.

- heuristic evaluation function: approximate the true utility of a state without doing a complete search.

Formalism

We will start with 2-player games. We can represent games with the following scheme.

Definition 1 (Game)

- Initial state: give board position and determine what player starts.

- Set of operators: defines a legal set of actions/move a player can make.

- Terminal test: determines when the game is over based on given state.

- Utility function: gives a numeric value for the outcome of a game… occurs only at the end. (example: in chess, the outcome is a win, loss, or draw, which we can represent by the values +1, —1, or 0.).

- If this were a search problem, then all we’d need to do is find a sequence that leads to us ending up in a terminal state deemed a winner. But we have an opponent to deal with.

- Thus, to compensate, our agent (which we will call

MAX) will have to find the best strategy that will end us up in a winning state, regardless of what the opponent (MIN) does. See how we will have to plan for the future? At each move, we must pick the correct move given all possible actions thatMINcan take.- Impossible for most games so we will have to approximate this using heuristics.

- Thus, to compensate, our agent (which we will call

It is important to understand how we can represent games as trees.

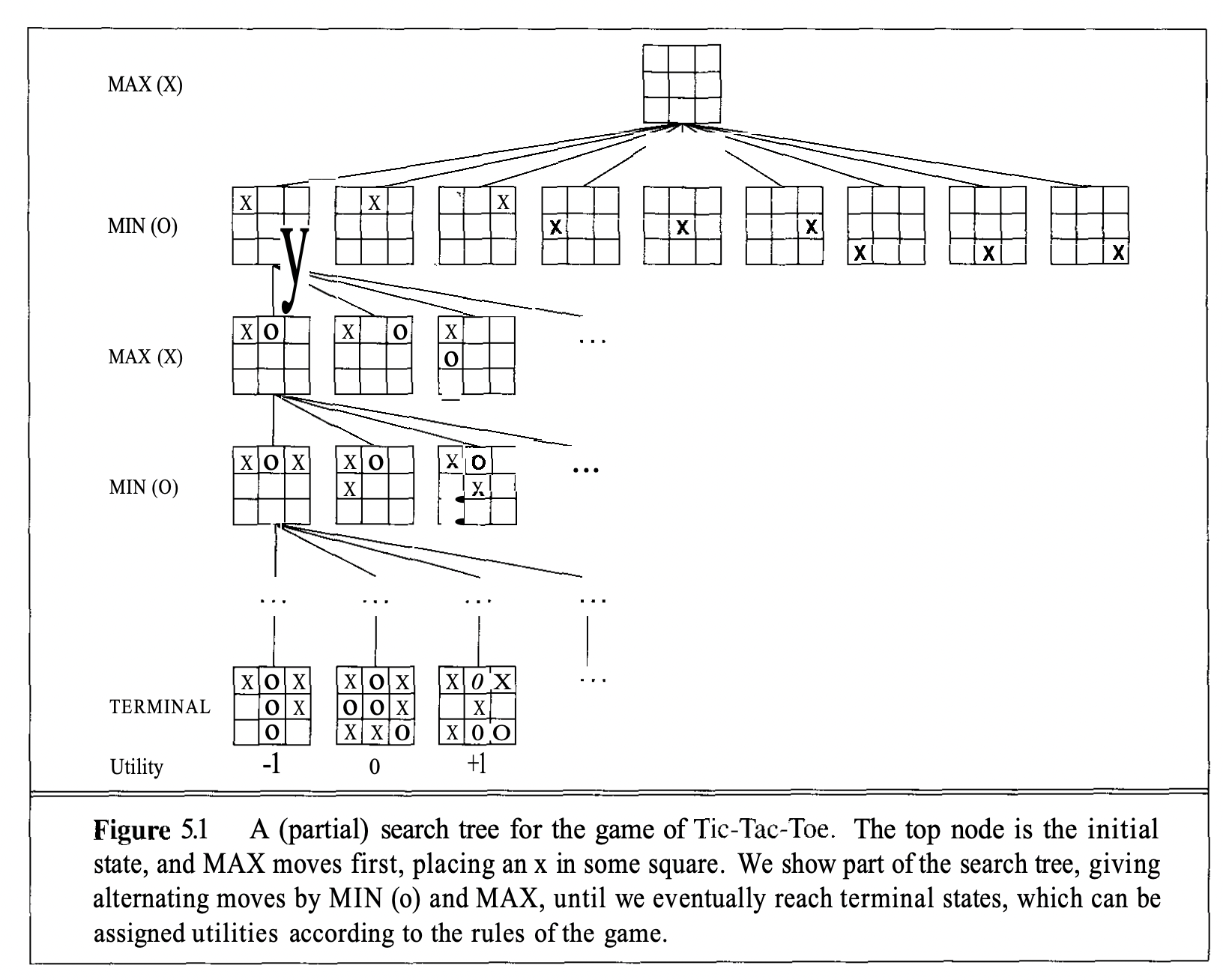

Here is a simple tic-tac-toe example:

The idea is that each, for each layer (depth-wise), we represent all actions the previous player took for each node/state. Then, the next layer is all actions the current player can take. In the above example, MAX starts the game and produces 9 different nodes/states for the next layer because they can make 9 different moves given the current state of the board.

II. Minimax algorithm

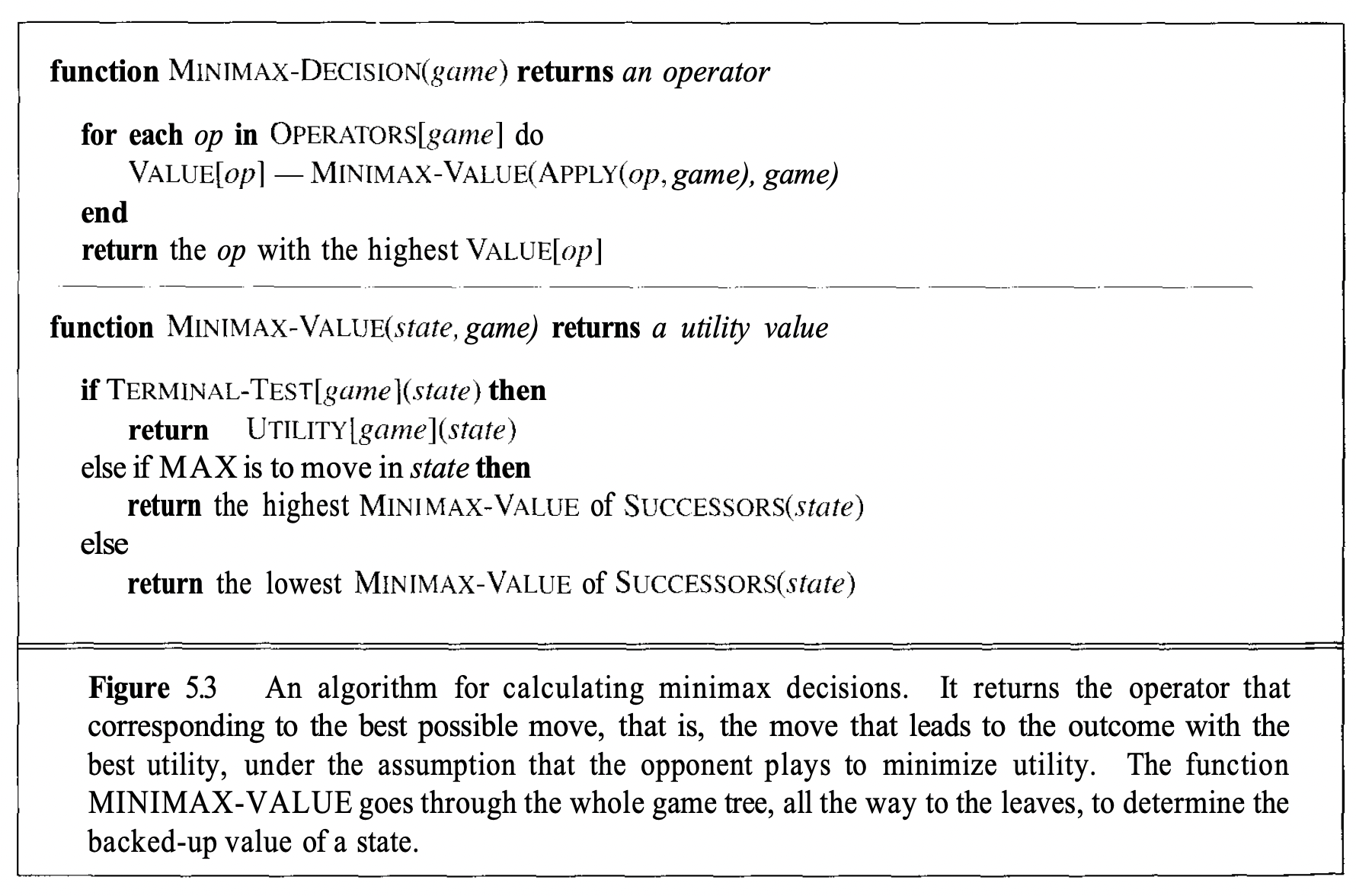

- Algorithm for determining the optimal strategy for our agent (

MAX). - High-level pseudocode:

- generate entire game tree from starting position/player (accounting for all moves)

- At terminal states (leaves), apply the utility function to each terminal state to get its value.

- Use the utility of the terminal states to determine the utility of the above layer states. At each sequential layer above, if it is

MIN’s turn, choose the action with the least utility in the successor layer. ForMAX, choose the highest utility.

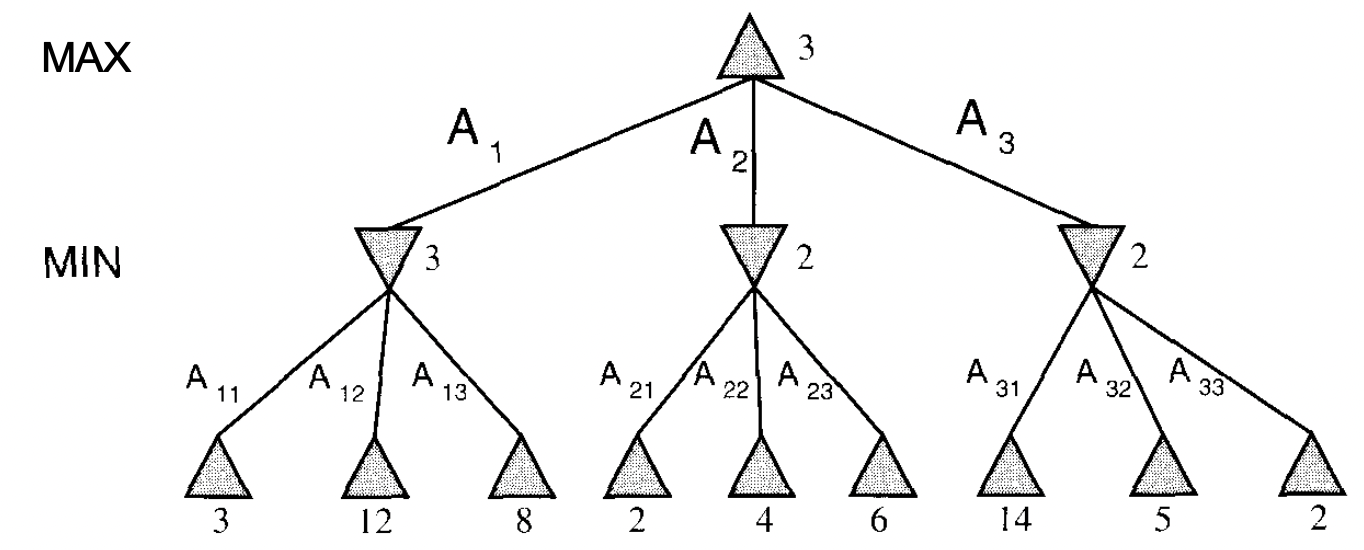

Here is the tree:

Key note: we operate under the assumption that MIN will choose the minimum utility (from the perspective of MAX). This makes sense if you think about it: the utility function will determine the utility of the action/state for MAX (our agent). So MIN will logically pick the worst move for us and the best move for them. Drill this idea in before moving on. Then minimax makes sense given the name.

the runtime is

\[ O\left(b^m\right) \]

where \(b=\) num legal moves and \(m=\) maximum depth of the tree.

The formal algorithm can be described recursively as follows.

Summary:

- See definition of game. Represent this as a search problem tree.

- Each layer in tree corresponds to the moves the predecessor took and the successor layer represents all the moves you can take.

- Calculate utility for each node in the tree based on the

MIN/MAXassumption and utility function. - Choose sequence/branch that maximizes the utility.

III. Imperfect Decisions

- Of course, the approach above is impractical and not efficient. To compromise, we introduce some new techniques which avoid having to traverse through the tree to the leaves for the sake of calculating the utilities.

- Shannon’s approach: don’t go all the way to the terminal states… cut off search earlier and apply a heuristic evaluation function to the leaves of the tree.

- For this, we alter minimax in two ways:

- Replace the utility function by an evaluation function \(\texttt{EVAL}\).

- Replace the terminal test with \(\texttt{CUTOFF-TEST}\).

Evaluation functions

Definition 2 (Evaluation function) An evaluation function returns an estimate of the expected utility of the game from a given position.

- However, it should be clear that the performance of a game-playing program is extremely dependent on the quality of its evaluation function.

- Though, how should we measure “quality”?

- We want:

- Terminal state should result in same under utility and \(\texttt{EVAL}\).

- Efficiency

- Accurately reflect the actual chances of winning.

- We want:

In chess, it is common to calculate a material value of the state of the game for the agent. For example, each queen is worth \(9\) points, each rook is \(5\) and so on. Thus, we can have:

\[ \operatorname{EVAL}(s)=w_1 f_1(s)+w_2 f_2(s)+\ldots+w_n f_n(s) \]

where, for example, \(w_1=9\) and \(f_1(s)=(\text { number of white queens })-(\text { number of black queens)}.\)

Most chosen \(\texttt{EVAL}\) functions take this form: linear in the sum of weighted features. However, it is also possible to learn a nonlinear \(\texttt{EVAL}\) function in the form of a neural network.

Cutting off search

Ok cool… we now know a way to approximate utility through a weighted linear combination of features representing \(\texttt{EVAL}\). Now how do we control the amount of search?

- standard approach: set a fixed depth limit, so that the cutoff test succeeds for all nodes at or below depth \(d\). The depth is chosen so that the amount of time used will not exceed what the rules of the game allow (Russell and Norvig).

- A more advanced approach: iterative deepening.

IV. Alpha-Beta Pruning

Allows us to ignore portions of the game search tree that do not affect the outcome.

Basically, at each layer, we can ignore the rest of the tree for the part that we don’t pick based on minimax.

Summary

Note:

- uncertainty constrains the assignment of values to states

- we talked about deterministic games (i.e., without chance nodes). See section \(V\) for nondeterministic games.